100 Days of Franklin - Week 7: Neck and Head

Neck and Head week! After a challenging foot week, we’ll go for a more relaxed head and neck week.

Day 43

We’ll spend a bit of time with the neck this week, but soon move up to the head.

For today, spend some time exploring the range of motion of your head (neck, face, ears, etc. included). What moves? What doesn’t? In which directions? For what reasons? What is articulated with what?

Day 44

Let’s first try to improve our sensation of our head balancing on top of our neck. On a well aligned body, this happens quite effortlessly. But it can take very little for the head to not be able to balance easily, and then it takes a lot of muscular effort.

At any point during today’s images, feel free to take the time to find your body’s best alignment. Roll your feet, do some pelvic tilts, work on your axis, work on your spine. Take some time in constructive rest. Do some tapping.

-

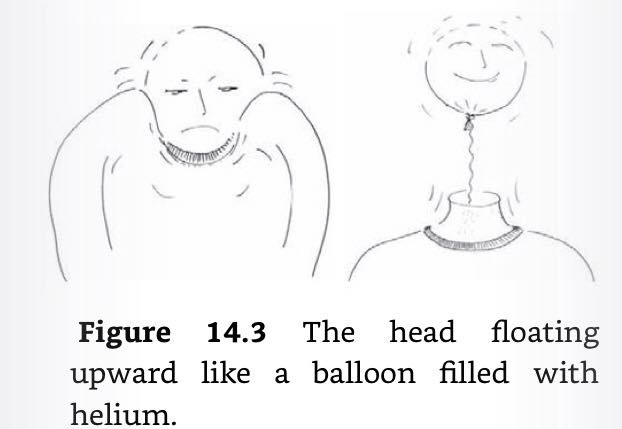

Imagine your head as a baloon. It is filled with helium, and is “resting” on the light air inside it. It is attached to the rest of your body by a long, soft string. Sometimes, we tie our head down because it’s scary for it to be so far away, let go of these ties, one by one, and let your head float softly but securely away.

When your head loses balance at the top of your spine, picture it bobbing back up, supported by the helium inside.

Don’t panic!

-

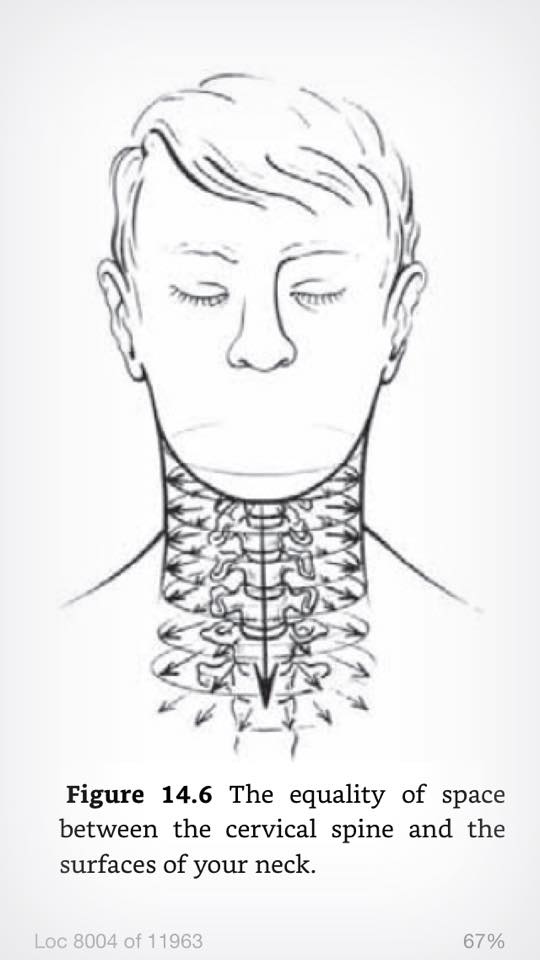

Visualise your cervical spine. Going up from the thoracic spine which is back of your axis, letting the spinal processes be very “touchable”, the cervical spine curves back in and up, completely rejoining your central axis.

Imagine your cervical spine is at the centre of your neck, equally far away from every side.

Imagine all sides are equally soft, but equally supportive.

-

We often support our head from the back. Touch your thyroid gland, on your throat, a few cm above your sternum-clavicle articulation. Imagine a balanced, relaxed, supportive thyroid, to help support your neck from all sides.

-

Imagine the neck as the top of an inverved cone, starting down at your pelvic floor. Your head is not just supported by your neck, but by your whole body.

Day 45

Today, we’re going to look at how the head moves and articulates with the neck.

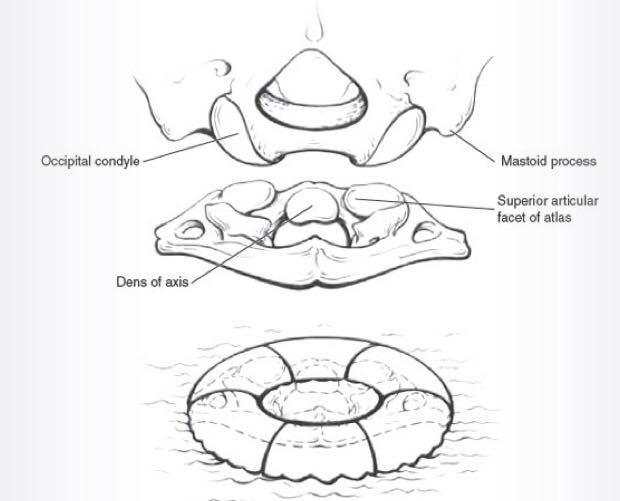

Just like the pelvis has its sitbones, the skull has two occipital condyles at its base. These condyles rest on the atlas, the topmost cervical vertebra, which looks and acts like a lifesaving ring, cradling the skull.

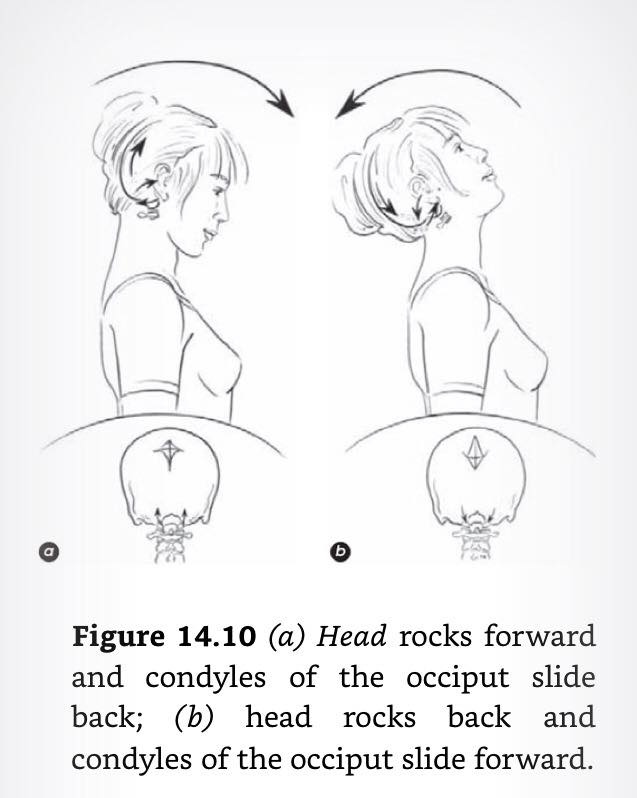

These condyles mostly allow the skull to nod forward and back (with a small amount of leeway in other directions).

Let’s relate the upper (cranium) and lower (pelvis) condyles.

Sitting, rock back and forth on the sitbones. Picture a similar rocking movement, happening at the articulation between the condyles and the atlas, with the convex condyles nested comfortably in the concave atlas. As the head nods up/back, the condyles spin, sliding forward. As the head nods down/forward, the condyles slide back.

Picture your central axis. Just as the sit bones are located symmetrically on either side of this axis in the frontal plane, so are the occipital condyles.

From standing, descend into plié, feeling both sets of condyles spreading apart, along with the base of the skull and the whole pelvic floor. As you extend, this image reverses, with a slight difference - as the pelvic floor and sit bones narrow, the base of the skull and occipital condyles feel greater lift and float away from the neck.

Day 46

We go down one vertebra!

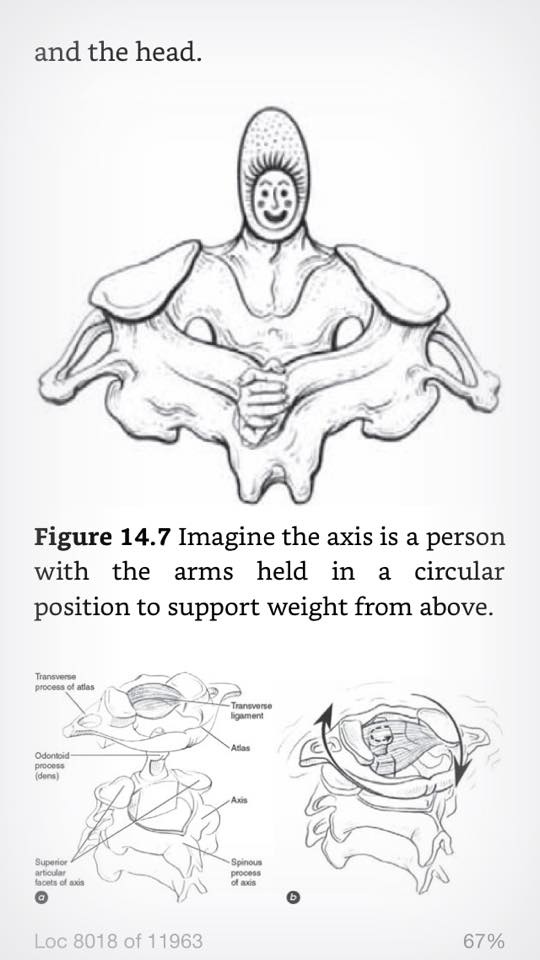

Below the atlas is the axis. This little bone is really cool. It has a little tooth sticking up from its front called the dens. The dens fits neatly into a gap in the atlas, created by an inner transverse ligament and the inside-front of the atlas. This basically provides an axis for the atlas to pivot around - and a large proportion of the left/right rotation of the head.

-

Place your fingers on the bones behind your ear lobes. There are some bony prominences there. Below them there is a gap (where the donut shaped atlas is) and below that, a tender spot (where the wide transverse processes of the axis are - this is where the levator scapulae, and a bunch of other nerves and ligaments connect). The occipital condyles and the dens are on the line between your fingers, with the dens pretty much exactly on the central axis of your body.

-

Move your head left and right. Picture the smooth movement of the atlas on the dens of the axis. The axis also has its upper surface made smooth to support the gliding of the atlas. As you turn your head the the right, imagine the dens pivoting relatively to the left, and vice versa.

-

As you move your head to the left, towards the end of this rotation, you will feel your head banking, with your eyes looking slightly up. This is because ligaments attached to your skull are pulling “down and round” on the back right of the skull’s opening, to assist in rotation to the left. You can feel the same phenomenon happening to the right (back left of your skull goes down, head tilts so the eyes look up)

-

Roll your neck forward. Some of this rolling is in the lower cervicals, some of it is in the occipital condyles/atlas articulation. From here, rotate your head to the side. You will feel the portion of condyle/atlas rolling being “undone” by the tilting of the previous image. This can help visualise the portion of nodding that happens between atlas and condyles (as opposed to the rest of the cervical spine).

-

Imagine the slope of the axis is such that when the atlas rotates on top of it, it goes down a gentle slope. As you rotate your head left, the left side of your atlas goes down and back; the right side of your atlas goes down and forward. This lowers your skull slightly and gives your spinal cord room to rotate without over extending or shearing it. As you bring your head back to neutral, your atlas coasts back up onto the shoulders of the axis, gently raising your head and lengthening your cervical spine.

Day 47

Constructive rest Friday! Lie in constructive rest for 7-14 minutes. Let the spine and neck lengthen as you review the images of this week.

- Images for a free, supported head

- Images for nodding forward and back

- Images for rotating side to side

Day 48

From the atlas we move up to the skull. Its opening is in the horizontal plane, just behind the occipital condyles, allowing the head to be lightly perched on top of the spine. From birth until age 18, the skull’s multiple bones gradually suture together - but these sutures still allow a small degree of mobility, and we can benefit by thinking of the skull as a flexible structure.

Touch the forehead, called the frontal bone, and glide your fingers over the top of the head (which consists of the two parietal bones) to the back of the head, the occipital bone. The occipital bone extends under the head to areas you cannot touch and forms the back part of the base of the skull. Return to the front of the head and touch the frontal bone over your eyes. If you move your fingers down the sides of your eyes and to the rear, you will discover a ledge called the zygomatic bone. Above the zygomatic bone you will find the sphenoid bone, and if you continue along the zygomatic to the rear, you will reach the temporal bone, which extends above and behind this area. We’ll explore the face and jaw area at another time.

Imagine your head as being perched effortlessly on top of your spine in all situations. Initiate various kinds of movement from your skull and notice how your spine and the rest of your body are affected. Imagine the atlas supporting the occipital and the occipital supporting the rest of the skull.

Place your finger tips under the back of the jaw. Push gently against them and then upward. Imagine the neck lengthening with no voluntary effort whatsoever.

The pelvic halves and temporal bone are related through bone rhythms. Hold on to your ears. As you go into plié, the ASIS and temporal bones go in. As you extend, pull on your ears and think of the ASIS and the temporal bones flaring out. As you plié, relax the pull. Do this a few times and notice how it affects your plié and posture.

Day 49

A complex set of muscles assist the axis and atlas in keeping your head afloat, acting like a set of ropes and pulleys. The suboccipitals are the deepest of these muscles, linking axis and atlas to the occipital bone. Actively trying to lengthen your neck will prevent the suboccipitals from properly doing their job.

Above (towards the skin) the occipitals comes the splenius. This means “bandage” in latin, and bandages from the spinous processes of the lower cervicals up to the lateral rear of the occipital bone.

Above the splenius is the trapezium.

Imagine the splenius as a spiraling bandage that extends all the way past the ears and above the skull.

Imagine the muscle fibres of the splenius lengthening. Let the spinous processes of the cervicals and upper thoracics melt down as the head floats up.

Picture the different kinds of support provided by the suboccipitals, in both lengthening and shortening. Some connect the spinous process of the axis with the transverse processes of the atlas (useful in rotation, among others), others connect the spinous process of the axis with the occiput (also useful in rotation and in lateral flexion). Others connect the spinous process of the atlas with the occiput (useful for nodding). Others connect the transverse processes of the atlas with the occiput. (useful for nodding in the other direction).

Picture all the ways these different muscles can lengthen and shorten in concert forming a tensegrity system that allows the head to float and move freely above the neck.